Two paths ::

My professional life is divided unequally into two parts. The shorter one was a 20 year stint as a researcher in medical labs; the second one, as an ornithologist, like a good second marriage, is still going after 42 years.

First career ::

Medical research

After graduation from college I spent 20 years in medical research laboratories working in a variety of fields – rickettsial diseases, vaginal and gastroenterological cytology, electron microscopy techniques, and immunochemistry. They were generally interesting and rewarding, but when I took my first job in California it was in a lab where medical research on animals was conducted. I spent 10 years in this field and became more and more uneasy with the use of animals in laboratory work, especially when it seemed not justified except as a means to a grant renewal. When I look back on this period I find that it included some wonderful friendships and some interesting work experiences but was dominated by the feeling that this was not where I belonged, nor what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. In 1968 the grant money ran out and I decided to quit, to try being an at-home mom to Lolly age 8, and do volunteer work. Eric had tenure and had been promoted and for the first time in our marriage we were financially comfortable enough for me to take some time off. For the next year I was very active in the League of Woman Voters and the Fair Housing Foundation, both interesting, but pastimes; and realized I could not stay on this course for the rest of my life. I was 46 and probably had the longevity gene that saw my mother and maternal grandmother live til their mid-90s, so half my life was yet to come.

Second career ::

Life with birds

I had become intrigued by birds and bird behavior a few years before on a visit to Bear River National Wildlife Refuge at Great Salt Lake when the nesting season was at its peak. There were families everywhere – herons and egrets, avocets, stilts, shorebirds, waterfowl, rails – it was an epiphany. Killdeer were doing broken-wing displays and there were chicks of all kinds and sizes. When we returned home I decided to teach myself about the local birds and began to do a weekly walk at the Long Beach Nature Center. Within a year I had a pretty good handle on the local birds, including their vocalizations, and found bird-watching engrossing. But identifying was not enough. I wanted to learn much more about birds, and particularly about behavior. So in the spring of 1970 I enrolled in a class in Ornithology at California State University Long Beach, having no idea it was going to transform my life. It was taught by Charles T. Collins who was maybe 30, and very new at teaching, having finished his PhD. only a few years before. I often think how lucky I was that he had come to CSULB to teach Ornithology just before I decided to go back to school. He was quite intrigued by having an older student and a great mentor then and thereafter. I was old enough to be the mother of most of the class, and was the only woman student. I loved (and aced) the course and Charlie talked me into going on for an M.A. It was 25 years since I had been an undergraduate and the idea was daunting. But he had no qualms about pushing me and for the next 30 years played a huge role in my life as friend, mentor, constructive critic, and initiator of fascinating projects. One of them was bird banding. That first spring he and Jay Sheppard (grad student under Stu Warter, the other Ornithologist at CSULB) set up a banding station in Morongo Valley in the upper Mohave Desert and I spent a week there learning to handle mist nets, trapping and banding spring migrants as they stopped at the oasis on their way north. We caught over 1500 Wilson’s Warblers and I got a wonderful photo of Lolly holding one. I was learning so much so fast it was head-spinning.

In the fall I began a full load of course work, including Botany, Entomology, Mammalogy and other courses I scarcely remember. Botany came easily and Plant Taxonomy was definitely a favorite, but learning a whole raft of taxonomies taxed my middle-aged memory sorely. It was a time of social turmoil with race relations, the Vietnam War, the Women’s Movement, the marijuana culture, and the hippie movement all energizing what seems in retrospect to have been a stagnant post-war period. And what I was doing fit right in with these times – a wife and mother of 46 switching careers and in graduate school with a batch of young men (there were women grad students in Biology a few years later but not then) whose problems were legion. Head-spinning in retrospect.

My undergraduate degree was in Zoology and did not meet some of CSULB’s requirements for grad students, including Physics, which I had managed to wriggle out of. My science skills and interests have always been limited to the biological and not the physical sciences – struggles with undergraduate Chemistry had taught me to avoid the latter. There was no way I was going to submit to the punishment of a Physics course at my advanced age, and I was sure to fail. Somehow Charlie inveigled a waiver from the administration, the first of several he managed on my behalf, and I was off and away. And just in time, as the school initiated the requirement of a Graduate Record Exam the next year, and I would have surely failed that as well. I was a forerunner in the return-to-grad-school movement and it took awhile for universities to adjust their entry requirements for us; to take age and work experience into account.

A thesis was required for an advanced degree in Biology and another of my caveats was that I would not experiment on or kill another animal. Mine would have to be a field research project, and Charlie accepted that. Another stroke of luck guided my choice. The first federal Endangered Species Act that listed species was passed in 1970 and on it was the California Least Tern. There was little known about the bird’s breeding biology, only that it nested on the beaches of southern California and that its numbers had clearly diminished rapidly with the post-World War II development of this habitat. Charlie apparently realized that there was going to be a need for expertise on the management of endangered species and I apparently looked like a good candidate. There was a nesting colony within 5 miles of my home and that was great for me, with a small child at home. I started observing Least Terns when they arrived to breed in April

1970 and was immediately hooked. That summer I learned to take field notes, use an observation blind, band chicks, locate fledglings, and it was a whole, new, wonderful world. Lolly joined me often and was adroit at chasing chicks for banding, and what could be more intriguing to an 8-year old? Years later, as a grad student at UCLA, her summer job for several seasons was monitoring the colony at Venice Beach.

Mostly it was absorbing, challenging, do-able, and fun, but there were down times too. I remember vividly going to Palm Springs with Eric for a 25th anniversary weekend that December and being so anxious and depressed and sure I was going to flunk Entomology that I could not enjoy a holiday and we came home after one day. A heavy, steady rain didn’t help the situation. The course work got easier as I re-learned how to memorize and acquired the various taxonomies. But it was never easy like it was at 20 when one is still on the up-curve and can conquer the most unbelievable challenges. Writing a thesis was no problem, in fact I loved doing it. And in June 1972 I defended it and earned an M.A. in Biology. My thesis was published the Proceedings of the Linnaean Society of New York in 1974, along with two other articles on Least Terns (see Scientific Publications), thanks to Charlie’s efforts and connections. It was the first of many scientific publications, articles and books.

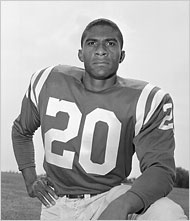

Professional football player, biologist and Tern specialist

I can’t resist an aside here to tell an anecdote. The author of one of the other articles was Milt Davis, who got his MA at UCLA in Biology when he was a professional football player for the Colts in the late 1950s. His thesis was a behavioral study on Least Terns at the Huntington Beach colony. He would spend the fall and winter playing football, and spring and summer doing research. He has a unique niche in history as the first (and perhaps the only) black/American Indian, professional football player, tern researcher. He went on get a doctorate at UCLA and to a career as a biology professor at Los Angeles City College. We met when Charlie was organizing the publication of our papers; he was a most interesting man, intriguing because of his diverse abilities, but not at all intimidating despite being very large and fit as one might expect. We got right down to tern-talk and I very much enjoyed the few encounters we had. When I googled him recently I learned that he had died in 2008 in Elmira Oregon, where he retired. His daughter, Dr. Allison Davis-White Eyes is currently Director of Indian Affairs at OSU.

[button link=”http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milt_Davis” color=”silver” newwindow=”yes”] Milt Davis Wikipedia page. [/button]

Endangered species research

All through graduate school I worried about my advanced age and about future employment. But two days after receiving an M.A. In June 1972 I was called about a job and that was the beginning of a long and varied career as a consultant on endangered species.

First adventure in tern research

A course in Evolutionary Biology taught by Ron Kroman had made a huge impact on me, and was the impetus for my first independent study. We learned about the road to speciation which can be summarized very briefly as a 3-step process – isolation, mutation, biological separation – that occurs over long periods of time. The isolation is usually geographic, with a group of like individuals becoming separated, as by an ocean or a mountain range. Then, and over a long period of geologic time, mutations occur that can cause the groups to diverge sufficiently that they are unable to mate. A capsule summary of speciation that can take a book to explain, but that is the gist of it. This knowledge caused me to think about relationships among the world’s small terns. There were at least 5 recognized on different continents. The most widespread was the European Little Tern, Sterna albifrons, with sub-species in Asia, Australia and North America.

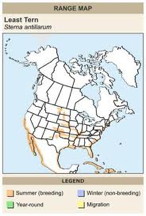

In the U.S there were 3, the east coast race Sterna albifrons albifrons, the birds along the Mississippi River drainage Sterna albifrons atholassus, and west coast race Sterna albifrons browni Mearns. There was no mingling of these 3 sub-species with the nominate race in Europe; the Atlantic Ocean was an effective barrier. And no known mixing of wintering birds. The east coast U.S. race was known to winter along the northern shores of South America, particularly in Surinam. And although it was not, and still is not, known where the other two races winter, there is compelling negative evidence they are separated. I wondered whether all these groups could really be one species, as was their current taxonomic status.

My close observation of the California Least Tern had made me aware of the importance of vocalizations in the bird’s breeding biology. Terns have many calls but the basic one is used between members of a pair and between parents and chicks. The chicks must distinguish their parents’ calls from all others in the colony within a day of hatching and respond only to them. The success of the system is based on this recognition. In a large colony where adults bring food to chicks which are roaming freely, they need to be able to find their own, as they are programed to feed only them. I decided that my first exploratory adventure would be to Europe to observe, and listen to, the Little Tern.

There was plenty of skepticism from colleagues about pursuing such a quest and I could extract no money from a granting agency, but my husband Eric was totally supportive and agreed that we should use our own funds and the idea became reality the next spring. In May 1973 I went to Norfolk, England to observe a large breeding colony of Little Terns at Blakeney Point. I was accompanied by a good friend, Peggy Garland, from Eynsham (where we had spent Eric’s sabbatical leave in 1977) and we traveled in her ‘caravan’ (British for ‘trailer’). When we got out of the car at Blakeney I heard a strange call and looked up to see a Little Tern carrying in a fish. It was a momentous moment in my life; I knew this bird was vocally so different from the Least Tern that they would not recognize each other. Evolution had been at work and the European and North American birds had diverged so they could never recognize each other by call. The primary vocalization was so different it could surely not be recognized by and American counterpart. After a summer of observation it was apparent that in most other aspects they were the same. Small morphological differences were documented later (using museum specimens) but it was the vocalizations that were important. The following summer (1974) I worked at the Massachusetts Audubon tern colony on Cape Cod and determined that the vocalizations and behavior of the eastern U.S. race could not be differentiated from the western one. So I wrote a paper called “Vocal differences between American Least Terns and the European Little Tern” and in 1976 sent it to Auk. Looking back, it was a bold move, a newcomer like me submitting to the most prestigious ornithological journal, but I really thought the paper conveyed important information about speciation and what the heck. When I received a letter of acceptance I danced around the house. Especially since one of the peer reviewers was Oliver Austin, the dean of tern research in the U.S. It was such a break-through, because I was brand new to research and a female to boot. He even wrote in his approving letter “Who is this Barbara Massey anyway?” In those years field biology was in the hands of the ‘old boys’ club’ but the writing was certainly on the wall and Oliver Austin was truly amazing in the way he accepted the changes in the wind.

Interestingly enough there have been important revisions to small-tern taxonomy in the past several decades. In 1983 the name of the species was changed from Sterna albifrons to Sterna antillarum, on the basis of vocalizations, and in 2006 genetic analysis resulted in an even more dramatic split with the genus Sterna carved into 4 groups and the Least Tern became Sternula antillarum. Same bird but taxonomy is altered by new information – behavioral in the first instance and genetic analysis in the second – and now there is no trace of the name I learned when I began to study them.

Of terns, rails and sparrows

Terns

The first talk I gave on the California Least Tern was at a Pacific Seabird Group meeting at Asilomar, a scenic conference center on an ocean bluff south of Monterey. There were two other women presenting, Judith Hand and Diana Matheison, and we all knew each other from previous ornithological meetings, although our areas of interest were very different. There were so few women in the field that the sudden influx of an actual group of three made the ‘good old boys’ uncomfortable. And the papers we presented were good, which either compounded their discomfort or made them realize that a new era was on hand. I was soooooo nervous, but it went well and I was very glad I had done it.A lot of good contacts came out of that meeting. Charlie Collins was the instigator, as he was for several decades thereafter, gently but regularly urging me to publish, to do talks, to go after opportunities. I could not have found a better mentor.In the summer of 1974 I went east to work at the Least Tern colony in Chatham, Mass, under the auspices of Ian Nisbet and Massachusetts Audubon Society. Another first – being part of a research team, living in a cramped cottage with Ian and two young male interns, learning to drive a big truck and a motor launch, working 18 hour days and sometimes sleeping on the beach next to the colony to get a 24 hour record of activity. Monomoy Island, 8-miles long and uninhabited except by birds, lay close off-shore and was reached only by boat. Large numbers of Common, Arctic and Roseate Terns nested there, but the Least Terns were on the mainland. Besides being paid a stipend for doing tern monitoring, I was observing and listening to these birds for my own research. (Later, in 1981, I went to Wichita, Kansas and found the Interior Least Tern, a bird of the Mississippi River drainage, indistinguishable from the other two.)

2-day old chicks

I was asked to do the first statewide survey of Least Terns in California in the summer of 1975 . I visited every known colony from Imperial Beach to San Francisco Bay and found approximately 600 breeding pairs. With such a small population, no wonder it was an Endangered Species.

There were two known breeding colonies on the west coast of Mexico but no one had ever explored Baja California to see if the birds nested there. So in 1976 I organized a small caravan to explore Baja California for nesting sites. This was another instance of colleagues voicing negative opinions about our prospects. But I felt certain that the terns did not acknowledge political boundaries and there were certainly many appropriate sites on the peninsula for them to breed. And at our first stop in Estero de Punta Banda just south of Ensenada, we found a small breeding colony. And another in San Quintin, the next estuary south. They were nesting all down the peninsula with a large colony in La Paz.

In 1978 I was awarded a $10,000 contract to do a project which I cannot now recall. The important thing was that this huge sum of money allowed me to travel in pursuit of tern research. My interest in small terns had expanded to a world-wide scope after returning from England. I was anxious to observe other sub-species of the Little Tern and other recognized species of small, black-capped terns on other continents. Australia offered both options. There were two birds to check out – the Australian Little Tern Sterna albifrons sinensis, a recognized race of the European Little Tern, and Sterna nereis, the Australian Fairy Tern, a separate species. Both bred on the south coast beaches of Australia although not together. I decided to go for two months – December and January – and could afford to pay Eric’s way to join me when he was free at Christmas. And Lolly, who was in high school, was the 3rd beneficiary and went to Israel for a month.

I flew to Melbourne in early December 1978 and was taking under the wing by Joan and Norman Vincent, tern watchers who treated me with the characteristically warm hospitality for which the country is famous. They shepherded me around to colonies of both species and equipped me with gear fir field work and camping, and also on some wonderful, non-vocational excursions up the Snowy River. I found that the two species differed in their vocalizations from each other and from the species I was so familiar with, but not so in behavior. I didn’t really succeed in clarifying my findings and was in something of a muddle about how to do so. Back home in late January I shelved the experience, giving only one talk and never writing a paper. There were many other projects in the hopper and I felt that sorting out the differences between small terns world-wide was too much to embrace. A rare instance of backing off!

In 1983 I took a trip to Galapagos and while eating breakfast in the grand old Lima hotel where we stayed, a woman who looked familiar walked over to our table because I looked familiar to her! It was Phyllis Faber. We had met at some wetlands meeting that I can’t recall. We had similar backgrounds, were even alumnae of the same college. After decades of another career and a life that included raising 3 children she was now a plant ecologist with a focused interest in coastal wetlands. That meeting sparked a good working collaboration and a friendship that took us on a trip to Madagascar a decade later, and many sojourns in the Anza-Borrego Desert. Phyllis had been a founding member of the board of the California Coastal Commission. We worked together on several projects involving wetlands, one on the ecology of riparian habitat in southern California is listed on the National Wetlands Research Center website . Later in the 1990s she was on the board of pro esteros.

For the next two decades my life was crowded with work and family events and the records are scant. The published papers help but many studies resulted in unpublished reports so I have to rely a lot on memories – some vivid but many vague – and the chronology is weak. But the major events were linked to Least Tern, Light-footed Clapper Rail, and Belding’s Savannah Sparrow research.

I had two partners during this period, Jon Atwood on the terns and Dick Zembal on rails. I worked mostly alone on the sparrows. Jon and I began collaborating in the mid-70s and continued until he left California after finishing a PhD. at UCLA in 1986. He was working on his M.S. under Charlie when we started. His project was a study of the Western Scrub-Jay on Santa Cruz Island. Seven seasons of intensive research, mostly at the Venice Beach colony, yielded information that resulted in a host of papers – on plumages, second-wave nesting, site fidelity, demography, and long term commitments and divorce, to name a few. By the time our team-of-two dispersed we had increased the knowledge of the breeding biology of the Least Tern enormously, which helped in the recovery process. During this period the California population grew from 600 to approximately 5000 pairs, an astonishing success story. And according to the 2012 census it is now close to 10,000 pairs.

In 1982 the Endangered Species had to be renewed and there was much concern the year before that it would be in trouble. There was public indignation about occurrences like the ‘snail darter’, a small endangered fish, holding up completion of the Tellico dam in Tennessee. Our experience with the act had been so productive I decided to write the story of the California Least Tern and the positive results we were getting. I sent it to Natural History, the magazine of the American Museum of Natural History in N.Y. and got a positive response. When they decided to publish it, they sent a photographer out to get photos and that was quite an experience. George Lepp, a very good professional wildlife photographer, arrived with a list of the photos they wanted. It was June and chicks were hatching, a great time for photography. I set him up in a blind and he spent several days obseving and photographing. The editor Liked what he was getting but kept upping the ante – after he got a difficult one of a pair copulating he wanted one of an egg hatching. Somehow I managed to find a setup and George spent hours in the blind waiting for the magic moment and got one of the best photos in the article. Happily, the 1982 version of the act passed with ease, and I never knew if our efforts played any role, but the article itself was a delight to me, and I am so pleased to have a PDF of the article for your review.

During the years of tern research there were many special people involved, and a large percentage were graduate students of Charlie Collins or Stu Warter at CSULB – Bill Schew, Kevin Foerster, Dennis Minsky, Kathy Keane, Connie Boardman, Ken Corey and Mark Wimer. My memories of all of them are very fond, we were a coterie of biologists committed to bettering the breeding life of the Least Tern. And they all went on to interesting careers, and most in field biology. Looking back they were the golden years of my working life; we enjoyed each other, we worked hard, and with the huge help of the Endangered Species Act, we made a difference.

My curiosity about other species of small terns worldwide never abated and during the 80s and 90s led to some adventurous trips to Australia, Ecuador and Namibia. No details here, but there are accounts of all of them in Adventures.

Light-footed Clapper Rails

Dick Zembal was also a grad student at CSULB, and joined the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on completion of his M.S. He later went to the Orange County Water District. Dick and I began observing Light-footed Clapper Rails Rallus longirostris levipes in the saltmarshes of southern California in1980, helped by a small grant from California Fish and Game. This bird was also on the Federal Endangered Species List and very little was known of its life history, so we were starting from zero. It was an entirely different study animal from the tern, being solitary, secretive, and non-migratory. The basic known facts were that it was resident in the coastal saltmarshes in southern California and one of 3 sub-species in the state. It seems never to venture above the high tide line, staying hidden in the tall cord grass (Spartina foliosa). Its presence is usually made known by vocalizations rather than by being seen.

We developed a censusing technique based on vocalizations – having learned early on that the rails call antiphonally at dusk and could best be counted through listening, with volunteers stationed strategically around the marshes. We censused the entire population in southern California and Baja California, banded individuals caught in traps in Newport Back Bay, and used radio-telemetry there to monitor daily patterns of movement. We documented the breeding biology of this elusive bird, and as there had been virtually nothing known of its life history when we began, everything we learned was of help in the recovery process. We worked together for 7 years until 1987 when I had to cut back on my commitments for health reasons, incurred mostly from overwork, and left Dick to continue alone. It was not a happy choice but it was clear I had to lighten my work load. Dick continued, and is still very much involved.

The captive breeding program he devised has resulted in the release of a significant number of young rails being released into the salt marshes of Southern California. For his contributions to rail conservation he won an award from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (see www.audublog.org).

Many memories flood into my mind about these years but two anecdotes are as vivid as yesterday. One was early on when Dick and I were experimenting with live traps to lay in the paths the rails made through the cordgrass while roaming their territories. A fellow researcher suggested trying a modified Bal Chatri used by falconers, as it worked for her on shorebirds. The Bal Chatri is a flat wire cage with a mouse in it, on the top of which one ties numerous loops of plastic fishing line. When the bird swoops on the caged prey it catches its leg in a loop that pulls tight and traps it. I deleted the bait and made the loops on a flat piece of hardware cloth and placed it along the shoreline where a rail made regular forays. Then sat down behind cover to watch. Very soon a bird came along, walking carefully as always, and put one foot right on the trap but with the toes splayed flat, then lifted the leg just as carefully and walked slowly on. Comical, we never thought to look at the gait of a sandpiper as compared to a rail. And I tried not to think of the hours of labor it took to tie those knots. We finally succeeded with large traps open at both ends into which the birds walked and triggered a spring that closed both doors. Much more laborious to make but effective and harmless.

The other memory is from one of our numerous trips to Baja California to do rail counts. It was after eating supper and we had built a driftwood fire at our marsh-edge campsite and the talk turned to religion. There were maybe 6 of us (I remember vividly that Dick Zembal, Pat Flanagan, Paul Jorgensen, Ray Bransfield were there but think there were several more), and all except me were raised as Catholics. Nevertheless we had all arrived at the same place as adults – agnosticism. We agreed that it was hard to reconcile fundamentalist beliefs with Darwinian evolution and although we all knew a few colleagues with had done so, there were none present. We gave creationism a good going over and went to bed content with the triumph of science over speculation.

Belding’s Savannah Sparrows

Belding’s Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis beldingi) is a sub-species of the Savannah Sparrow that resides in the saltmarshes of southern California. It is a sedentary bird, totally dependent on the habitat provided by southern California’s coastal marshes. In the 1970s it was added to the state Endangered Species list although never federally listed. I did a 5-year study on the population in Anaheim Bay (Seal Beach Naval Weapons Station) which included mapping territories, color banding adults, locating nests, measuring chick growth, etc. In 1977 I conducted a survey of this bird for California Fish and Game and found 1000-1600 pairs in the southern marshes (from Santa Barbara to the Mexican border). This report does not show up on Google, although several subsequent surveys are listed. In 1978 I wrote a monograph on the bird for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers which was printed in 1979 but never published. It was a summary of the bird’s life history with photographs by Dana Echols and plant drawings by Cameron Barrows. It is listed in my publications. Later, around 1990, Ken Corey and I did a study of the sparrows at Ballona Wetlands in Venice CA. Ken was, and still is, a U.S.F.W.S. biologist with a special interest in birds.

California Coastal Act

My life was periodically redirected into projects other than endangered birds, although I’m not sure just when most of them occurred. The first, though, was memorable. In 1973 I learned that the newly constituted Coastal Commission was starting to work on a coastal plan. The state legislature had dragged its feet for several years about passing a bill to protect our beleaguered coast, and the citizenry had finally rebelled and written Proposition 20, an initiative that easily qualified for addition to the ballot. It passed in the fall of 1972, and mandated the creation of a commission to write a comprehensive plan, allowing it several years to do so. If successful, the commission would become a permanent addition to state government. I made contact with the local office and found that a young planner named Praveen Gupta was in charge of the natural habitat and wildlife section, a seminal part of the plan. He was supposed to make recommendations on the relative values of what remained of natural coastal habitat from Santa Barbara to the Mexican border. He was bright and very concerned about doing a good job, but was trained as an urban planner and unacquainted with the natural world. What’s more, he was new to southern California. My appearance must have looked heaven-sent to him, and I was hired to steer him around the southern coast and teach him about its marshes, dunes, beaches, bluffs and river mouths and the native species associated on them. We became friends and toured the coast together and wrote the required report. And although I thought I was pretty knowledgeable at the start, it was a huge learning experience that required looking at natural habitat in a new way. And even more so for Praveen. Looking back I wonder at our temerity! The plan was accepted and in 1976 the legislature passed the California Coastal Act which gave both permanence and teeth to the commission. A seminal act in state history.

Naval base bird habitats

In 1979 I was asked to do an inventory of the plants and animals at Point Mugu Naval Air Station in Ventura County on the California coast. Ron Dow was a new presence at the base, hired to watch over its 2,500 acres of wetlands which were now protected under the new federal laws, the National Environmental Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act. Ron worked at the base for his entire career, retiring in 2009; and his one-person job grew to a staff of 22 with a budget of millions. For this project I asked Dick Zembal to join me and he took on the flora while I concentrated on birds. There were endangered species of both on the base. It was the beginning of a long partnership, as we began the study on the Clapper Rail soon after finishing the Mugu report. Later Dick was hired by the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station in the Mohave Desert to do a survey like we did at Mugu, and I joined in to help with the bird counts.

Huntington Beach Saltmarsh

Another unusual diversion from endangered species research was the designing of a saltmarsh in Huntington Beach. Caltrans was looking for a mitigation project because they wanted to do a bridge repair that would destroy some saltmarsh. They owned 25 acres of degraded former saltmarsh along the Pacific Coast Highway between the Santa Ana River mouth and Brookhurst Street and proposed that it be restored to a functional state. The problem was that there was no precedent for this, thus there was no one who knew how to do it. The only qualified person was Joy Zedler, a Botany professor at California State University, San Diego, who had her own wetlands lab and wa experimenting with growing saltmarsh plants. But she was far too busy. Somehow my name came up and I was asked to join with two agency biologists in designing the restoration. My colleagues were Paul Kelly from California Fish and Game and a 3rd person whom I can’t recall. We were a team of 3 who knew lots about denizens of saltmarshes but nothing about how to create one. But we actually succeeded in drawing up a plan with sinuous channels and the proper elevations for plants, and it became a reality in February 1989 when the dike was removed and seawater flowed into the sinuous channels we had designed. I monitored the regrowth of saltmarsh vegetation there for several years thereafter. The marsh has since been greatly expanded with restoration on the north side of Brookhurst Street.

For more information on this program please visit the following websites:

The L.A. Times environmental archives Feb. 18, 1989 article in the L.A. Times announcing the opening of Talbert Marsh.

Environmental Law Institute’s National Wetlands Awards Provides a short history on the project although the original three participants are not mentioned.

The Huntington Beach Wetlands Conservancy Official website for the present conservancy

Books

Guide to birds of the Anza-Borrego Desert

In 1984 Eric and I bought a funky desert hideout in Shelter Valley, an unincorporated community in the Anza-Borrego Desert. It is designated on old maps as Earthquake Valley, as a fault-line runs right through it. But that apparently was not a good come-on for real estate development when it occurred in mid-century so there was a name change. This purchase led to my spending a lot more time in the desert and eventually to the writing of my first book. But preliminary to that I did an 8-year survey of birds along a stretch of Vallecito Creek with Mike Evans, and we wrote a paper about it. That turned out to be a warm-up. I can remember exactly when the idea occurred to me to write a book. I had just bought a new guide to the geology of the desert (Paul Remeika and Lowell Lindsay. 1992. Edge of Creation. California Desert Natural History Field Guides, No 1.). It was a road trip through the desert highlighting the important geologic features. As I did a trial run along Route 78 with the book in hand I got the idea for a new kind of guide book on desert birds. One that would offer some scientific information as well as where-to-go, and how-to-identify birds. It would be based on two years of seasonal monitoring 4 times a year at 15 selected habitats in the desert – oasis, dry arroyo, mesquite bog, high desert chaparral, etc. I organized a small group of volunteers to do the counts then put the manuscript together and offered it to the Anza-Borrego Desert Natural History Association (ABDNHA). Betsy Knaak was, and still is, the executive director, and she was very enthusiastic and the preliminaries were soon underway. But very shortly thereafter a huge controversy erupted between the California State Park system and its support non-governmental organizations (NGOs), ABDNHA being the one for the Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. There has not been a lot of publicity about the battle between ABDNHA and the park but the gist of it was that the park system was in serious need of money and decided that the funds of its NGOs were actually the property of the state and decided to acquire them. ABDNHA and several other park NGOs fought back and one result was that ABDNHA seceded from its association with the state and went completely private, keeping its funds. But for a year activities like publishing were put on hold until the situation clarified. When it came out in 1998 I was very pleased with it. The format was attractive, the illustrations by Narca Moore-Craig were charming and I got lots of positive feedback from users. We had several book signing parties in Borrego Springs and San Diego, also fun. Store locations.

Guide to Birds of the Salton Sea

I decided this was a worthwhile endeavor and chose the Salton Sea for a second book. Dick Zembal partnered in the enterprise. This artificial body of water in far eastern southern California was a well known bird mecca. In winter it hosted thousands of waterfowl, Sandhill Crane, Eared Grebe, White Pelican, and White-faced Ibis; in summer Caspian Tern, Black Skimmer, American Avocet, Black-necked Stilt nested there; and it was a year-round home to Great, Snowy and Cattle Egret, Black-crowned Night Heron, Common Moorhen, Burrowing Owl, and Tree Swallow, to mention only a few of the 229 species we found on our counts. But major problems beset it. There was no outlet and the input of water came chiefly from the vast surrounding farms whose irrigation ditches drain into the sea. The salinity of the water, plus pesticide content, had created a toxic brew, and bird die-offs in some years were massive. The future of the sea as a bird refuge looked dim (and has become so) and we thought there should be a record of what was there at the time. The monitoring program was expanded from 4 times a year to once-a-month for two years at 15 sites (1999-2001). It was a far more difficult area to census because of the huge numbers of birds involved, but the commitment and energy of the volunteers was consistent and unbounded. The Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson was our publisher. Store locations.

Guide to Birds of the Rogue Valley

The 3rd and last of this series of guide books was begun when we moved to Ashland Oregon in April 1999. I realized very quickly that a guide book for birds of the Rogue Valley would be very appropriate. My partner was Dennis Vroman, a retired forester and excellent birder and botanist. We covered 20 sites and did most of the bird counts ourselves (no need to commute to birding sites, what a pleasure) and the book was published in 2003 by Oregon Field Ornithologists. Store locations.

Cascade/Siskiyou National Monument

I was “retired” but continued to be involved with birds. I spent a lot of happy hours exploring the area’s habitats, so different from southern California. After the book came an inventory of the birds in the newly created Cascade/Siskiyou National Monument. The monument had been created in 2000 as one of President Clinton’s last acts and it was the first ever set aside because of its impressive biodiversity. It is a patchwork of public and private mountain land that contains a wilderness area and is largely inaccessible. The bird list was anecdotal, there had been no systematic censusing of bird use by season, breeding birds, etc. So I gathered a group of local birders together and we began a 3-year period of monthly bird counts at 5 accessible sites in the monument at various elevations. The final report was sent to the local Bureau of Land Management and the data were entered in eBird.

Migratory Mysteries

Upcoming online publication

In 2010 a group of local birders joined me in a dipper watching project in Ashland. The American Dipper is an unusual passerine that lives only in streams and lakes in North America. It builds a nest next to, or in the middle of, or under a bridge over, a swift running stream. Its food is mostly the larvae of insects like Caddis Fly and Mayfly that are laid below the surface of the water on or under rocks. My experience with this unique bird before moving to Ashland was in summer in the High Sierras. Here I found they are present for much of the year in Ashland Creek that runs down from Mt. Ashland through the center of the town! We are now in the 4th year of this study and have learned many astonishing things (a Dipper webpage will be coming soon). In 2007 I started another book, this one on the migratory patterns of birds in the Rogue Valley and its surrounding mountains. Soon after becoming acquainted with the birds in southwestern Oregon I had realized that the montane habitat about 5000′ in the Klamath/Siskiyou Mountains was heavily used for breeding by migratory birds, then deserted in the autumn by all but a hardy few species that had adapted to life in the deep snow. Where did the migrants go for the winter? Most were long-distance travelers that went south to Mexico and south America, and this was pretty straightforward. But for some species like Song Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos migratory patterns appeared to be more complex. Again, serendipity came into play and I was soon immersed in a project involving stable isotopes in bird feathers and claws with John Alexander, director of Klamath Bird Observatory, and in examining the banding records KBO had accumulated over the past 16 years on song Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos. These may appear to be disconnected studies but they yielded new information on the mysteries of migration. Results of these side paths will be dealt with elsewhere (under the soon to be uploaded Song Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos webpages) as they are in need of a lengthy explanation. The book is called ‘Migratory Mysteries’ and explores the whole subject of migration here in the Rogue Valley. The book will be available for download from this website in the spring of 2014.

ADDENDUM

4/4/2019

Recently I looked thru this website and was astonished to find it so large and spanning my entire life – in spurts. But this last entry did not happen and I want to explain why.